Shared from GOLF.com | Written by Michael Bamberger | March 31, 2022

One hundred years ago, there was a poor nine-year-old Black girl in rural Mississippi, an orphan, fixing to turn 10 come summer. Could she possibly have imagined that she would someday have a biographer (in a manner of speaking) from a prominent white Southern family who now lives in a gleaming high-rise with a view of the Gulf of Mexico?

Not likely.

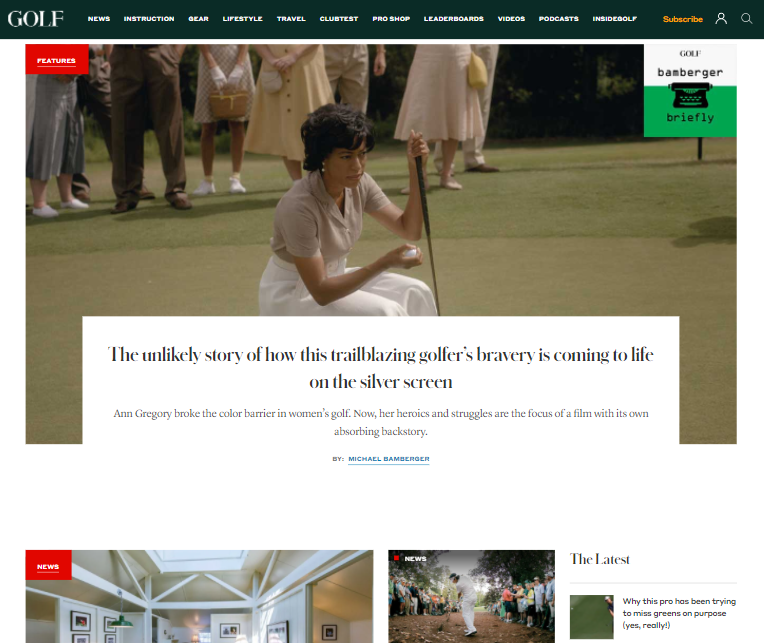

That girl, Ann Moore, grew up, married and moved to Gary, Ind. As Ann Gregory, she became the “Queen of Negro Golf” in various newspaper stories in the 1950s. You could also say she was — and is for eternity — the Jackie Robinson of women’s amateur golf in the United States.

Curtis Jordan, the biographer in the high-rise, has made a labor-of-love movie about Gregory. He never met her, but his mother did, once and memorably. Jordan’s film, Playing Through, is based on real events and it centers around an unlikely match between Gregory and a character shaped by Jordan’s own mother, Josephine Knowlton Jordan. Josephine went by Dadie. Her movieland equivalent goes by Babs.

In real life, Mrs. Gregory and Mrs. Jordan, as they were known in various sports-section write-ups, met in the second round of the 1959 U.S. Amateur at Congressional Country Club, near our nation’s capital. Mrs. Jordan was 2 up at one point in their match and even on the 18th tee. But Mrs. Gregory won the match, 1 up. That made all the difference.

Curtis Jordan’s mother was famously outgoing and chatty, as a student at the all-girls Madeira School in McLean, Va., as a summer colonist in Bristol, R.I., and as a sportswoman, wife and mother in Columbus, Ga. But her only son could never get his mother to tell the story of what happened that day. Not that he pried, or even tried that hard. That was not, he said, the Southern way. At least, not in his family, in Columbus, Ga.

Playing Through, produced by Jordan (and others) from a script he wrote, will have its premiere at the Sarasota Film Festival on April 2. It will also be available for downloading through the festival’s website. In May, it will be shown at the Harlem International Film Festival.

The origin story behind the movie’s fictionalized script is unlikely. When Gregory took up golf in the 1940s in Gary, the only place she was allowed to play was a scruffy nine-hole public course. The city-owned 18-hole municipal course was for white golfers only.

That the movie got made at all is nearly as unlikely.

Curtis Jordan, who is 70, spent decades as the head rowing coach at Princeton, coached on many Olympic rowing teams — and had never written or made a movie before. (His uncle, Gunby Jordan of Columbus, began the Southern Open which, for more than 30 years and under different names, was a PGA Tour event.) Jordan had no contacts in the film business, an industry that is a strange brew of agents, managers, actors, casting directors, location scouts, best boys and the rest.

One day, after struggling to find a person who could even help him find a person who could play Gregory, Jordan began entering various words and phrases in a Google search box. Acting experience was not among them. He stumbled upon the name Andia Winslow and sent her a direct message via social media. Winslow had never acted before, but she had a presence. Also, in an earlier life she played on the Yale golf team. In fact, she was the first Black woman to play Ivy League golf.

By pure coincidence, Winslow and her family knew Gregory’s daughter, JoAnne Gregory Overstreet, a retired school teacher who lives in Las Vegas. The two families met and became friends in Alaska. Overstreet’s husband, Louis, was then a civil engineer working on the Trans-Alaska oil pipeline. The Overstreets and the Winslows were part of small social group of Black families from the Lower 48 who found themselves living and working in Alaska.

I stumbled into all of this.

In 2020, after the death of George Floyd, I began writing a series of pieces about Black golfers, women golfers and people who found their way to golf from unlikely backgrounds. David DeNunzio, GOLF’s editor-in-chief, suggested I write about Gregory. I knew nothing about her and quickly learned that in 1956 Gregory became the first Black woman golfer to play in a U.S. Women’s Open and, two months later, at age 44, a U.S. Women’s Amateur. After that piece was published, I heard from Curtis Jordan, who told me about the movie he hoped to make. That was maybe 15 months ago, not even. And now he has a movie.

Sam Burns won the Valspar Championship at Innisbrook, near Tampa, on Sunday, March 19. The next day, I was in Jordan’s home in nearby Sarasota, with its spectacular Gulf views through a wall of floor-to-ceiling windows. After some chitchat, Jordan’s wife, Paige, hit a button. Through the magic of automation, the curtains closed.

Our focus was away from the sea and toward a large, elevated flat-screen TV, on which Jordan played long clips from Playing Through. I saw enough of the movie to say that the circa 1959 sets and costumes and artifacts — the caddie bibs, the golf clubs, the cars — were spot-on. The magic of moviemaking. I’m rooting for this film, but I don’t know much about the story it tells. I do know it is not one big lovefest.

“I knew nothing about this story until 1991,” Jordan said. A friend had called to tell him his mother was mentioned in a story in a new issue of Sports Illustrated. The piece was actually an excerpt from a book by Rhonda Glenn, an historian of women’s golf.

Glenn describes how Gregory was not allowed to attend a dinner for contestants in the Congressional clubhouse, at that ’59 Amateur. Glenn describes how her caddie was fired, by the club, for his exuberant response to Gregory making a birdie, to Jordan’s bogey, to win their second-round match. Glenn writes about how the club president invited Gregory, after her third-round loss, to return to Congressional anytime, and quotes Gregory: “I thought, He’s got to be crazy! I would never come back there to play after all of the things they put me through.”

There actually is no mention of how Dadie Jordan handled Gregory’s win, and her own defeat, in the 1991 piece. By then, Jordan was leading a life unlike the one she knew in 1959. She had divorced her husband, moved from Columbus to a ranch in Arizona and become a horsewoman and harness-racing driver. Still, Jordan Curtis could not engage his mother on the subject of the second round of the 1959 U.S. Women’s Amateur at Congressional.

Curtis has an idea about why: He suspects his mother, a woman of her time and place as we all are, was less-than-gracious to Mrs. Gregory, the older, working-class, public-course Black woman to whom she had lost. Despite his inability to learn more from his mother, that day in 1959, and that second-round match at Congressional, got lodged in Jordan’s mind.

“I had written a screenplay, not knowing what I was doing — I had to find books about how to write screenplays — and my plan was to turn my script over to experienced screenwriters,” Jordan told me. “And when I did, they were like, ‘And later in life the two women reunited and became the best of friends.’ And I’m thinking, ‘No, that’s not it at all.’”

Jordan’s aim was to capture his mother’s time and a place, and Gregory’s time and place, in all its social and racial complexity. “My mother was not an overt racist,” Curtis Jordan said. You didn’t see her racism in how she spoke to Black workers in her home, he said. But listening to Jordan, I got the sense that his mother did not even believe in separate but equal. More like separate and unequal.

In the movie, a club member with a gravelly voice looks through a clubhouse window at the course and summarizes the impending match this way: “Colored versus white. North versus South. Wealthy versus working class.” In real life, Dadie Jordan failed to represent her race and class in that match. In victory — and by all accounts in defeat, too — Gregory represented a more idealized future. Painfully, all these years later, Curtis Jordan will tell you, we are still working toward that future.

Curtis Jordan is not a writer, but he wrote a screenplay. He’s not a filmmaker, but he made a film. He’s not a golfer, but he made himself knowledgeable about the game. He’s not a sociologist, but he knows what it was like, as a wealthy white country-club kid in Columbus, Ga., to be raised more by his Black nanny than his white mother. It informs his life and his movie.

He wrote this line for a character named Ann Gregory but Ann Gregory surely thought it to herself: “Sometimes in life all a person needs is a chance to prove themselves.”

Nobody gave Gregory that chance. She gave it to herself, as a birthright she could recognize, even when others could not.